Why I’m against merging pull requests in squash mode or rebase mode?

/posts/git 2019-07-10 You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.

“Hotel California”, the Eagles

[DISCLAIMER]

-

The post is opinionated! GitHub provides three different modes for PR merging. Each is described very clearly in the official doc “About merge methods on GitHub”. I’m not going to repeat how they work under the hood. Rather, I’d try explaining why I think there should be only one option – the merge mode.

-

After being heckled by so many pathetic people who consider English as a privilege of westerners, let’s make this clear. I am Chinese and I wrote this post in English. If you cannot read this, learn English. It’s not my fault.

A quick comparison.

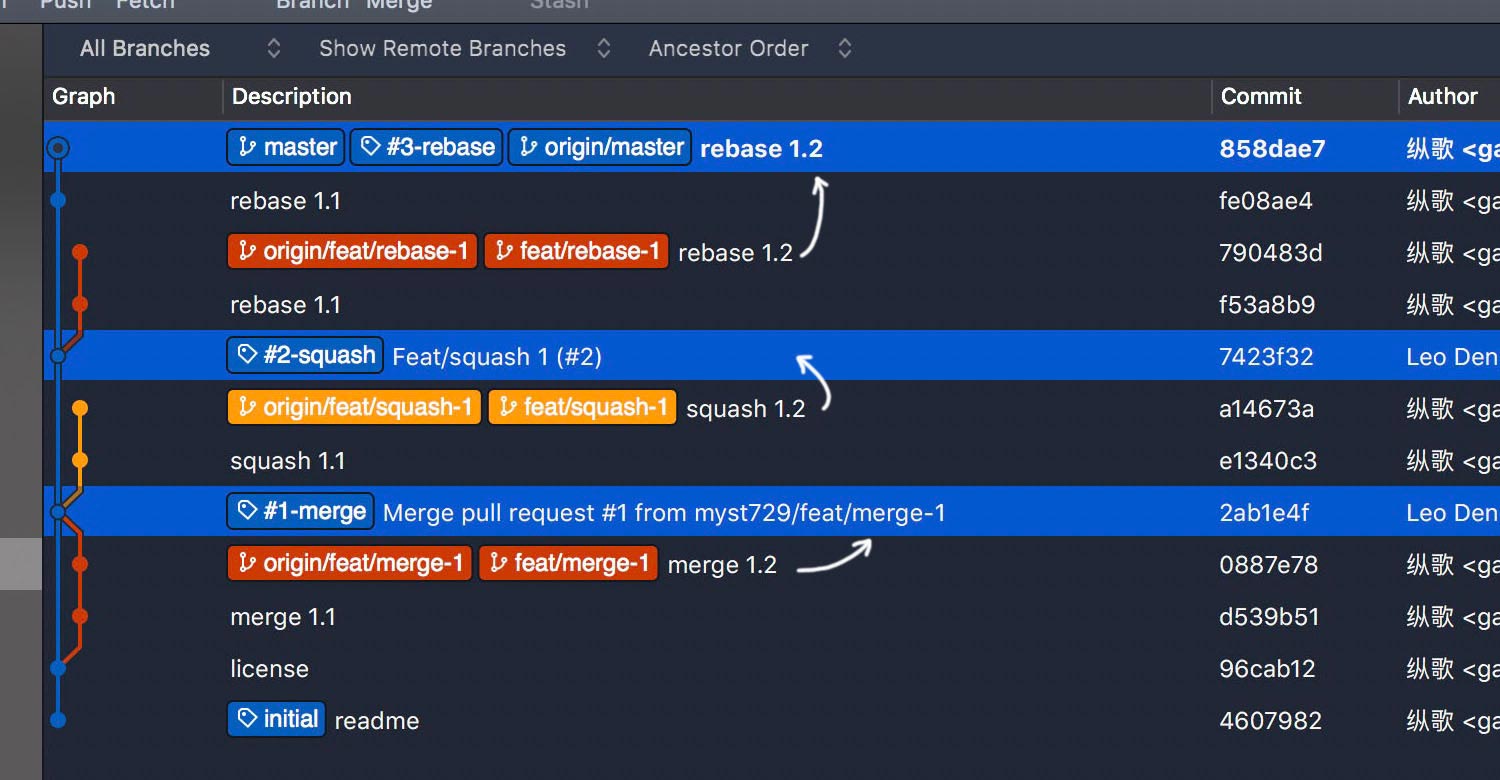

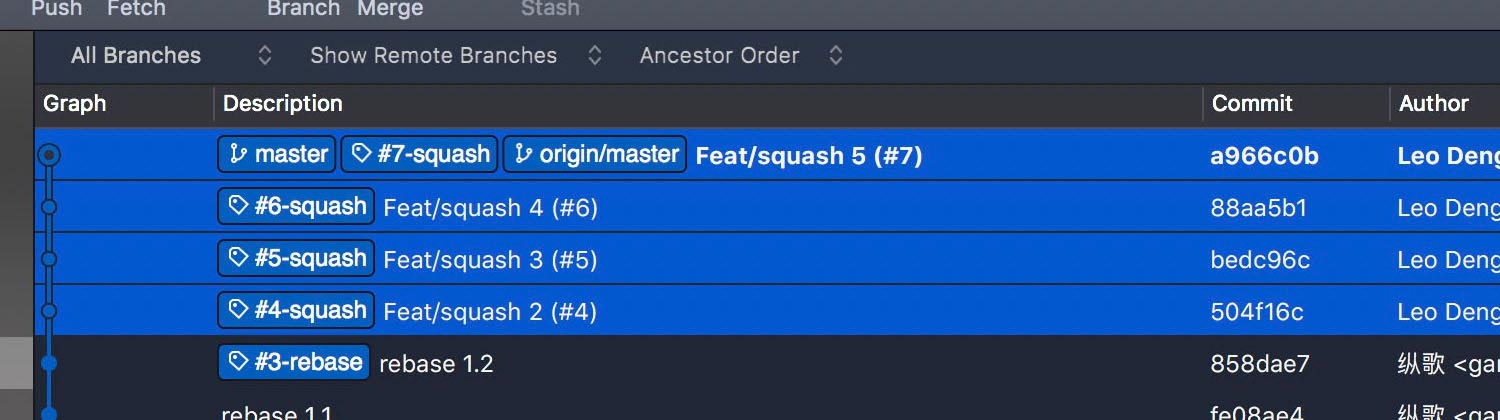

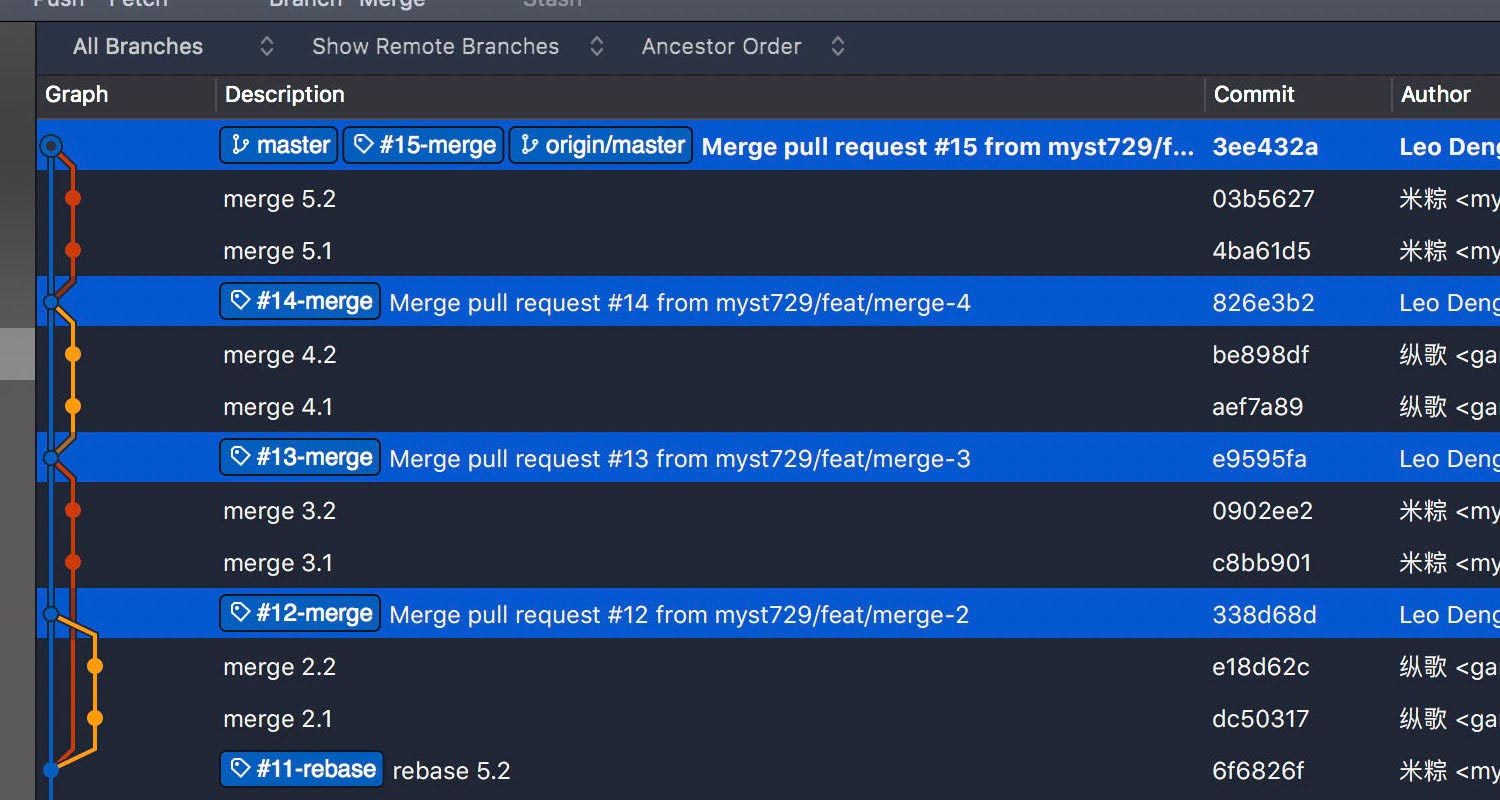

First off, let’s give all three modes a try with pull requests #1, #2 and #3. To be clear, I tagged each PR merge with its PR number and merging mode.

- In merge mode, an ugly sideway out-and-in retains all details in developing the feature.

- In squash mode, changes are combined into a single commit on master branch, looks quite neat.

- In rebase mode, all commits are added onto master branch individually, a little verbose.

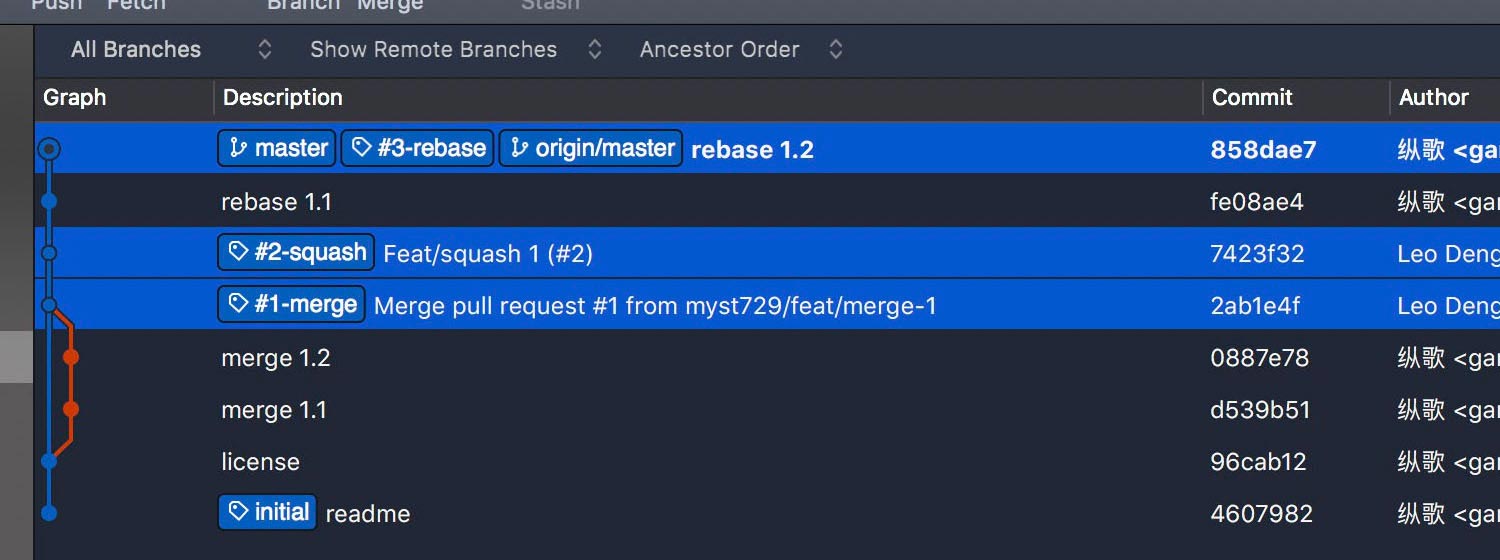

Consider a project that has been developed for months. There could be hundreds of frustrating feature branches. In squash mode or rebase mode, these branches are isolated and inactive after PRs get merged. To keep the repository clean, we may routinely delete the merged branches.

What happened?

- In merge mode, an ugly sideway out-and-in, barely changes.

- In squash mode, details are gone with the feature branch.

- In rebase mode, details are retained at the cost of “verboseness”.

What’s the problem with squash mode?

It is important to retain the development details. In real projects perfect rarely exists. We make mistakes all the time. Wrong decisions, wrong codes, wrong commits, wrong everything. Some of them are meaningless, such as typos, or forget to switch branches. These mistakes could be dropped because they don’t provide helpful information along the time. That’s why git commit --amend, git reset or squash and drop options in git rebase --interactive were designed. But not every detail is meaningless and should be thrown away. For instance, if I realize that I’ve made a wrong technical design decision, and decide to revert some commits, it makes sense to let my cooperators know why and in what condition it doesn’t work. The point here is, the verboseness in rebase mode is not a bad thing. On the contrary, it’s very useful after years of active development.

You don’t agree? Well, maybe I was wrong. You do like tons of dead feature branches. If this is what you want, close the page and we are good like always.

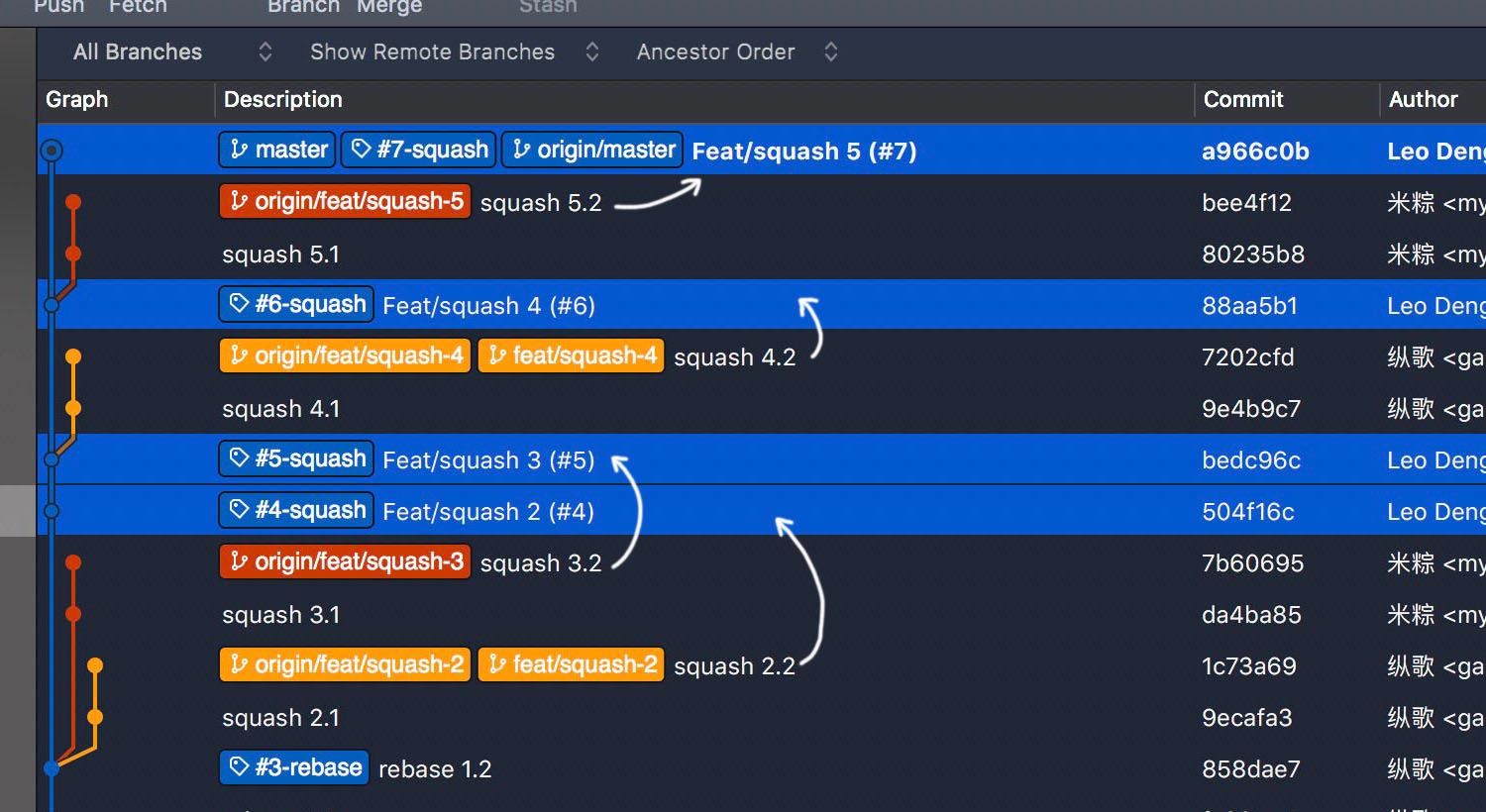

Another problem is about cooperation details. Teamwork is very common in real projects. The log graph may typically reach such a state. Do notice that PR #4 and #5 are branched from the same commit 858dae7, while #6 is branched from bedc96c and #7 from 88aa5b1. They’re very different – #4 and #5 are developed in parallel, #6 is a prerequisite for #7.

It’s not easy to distinguish PR #4 and #5 along with their corresponding feature branches. How does it look after the housekeeping work? Can you reasonably conclude that #4 and #5 are developed in parallel, while #6 is a prerequisite for #7?

Nuh. Cooperation details are lost too.

What’s the problem with rebase mode?

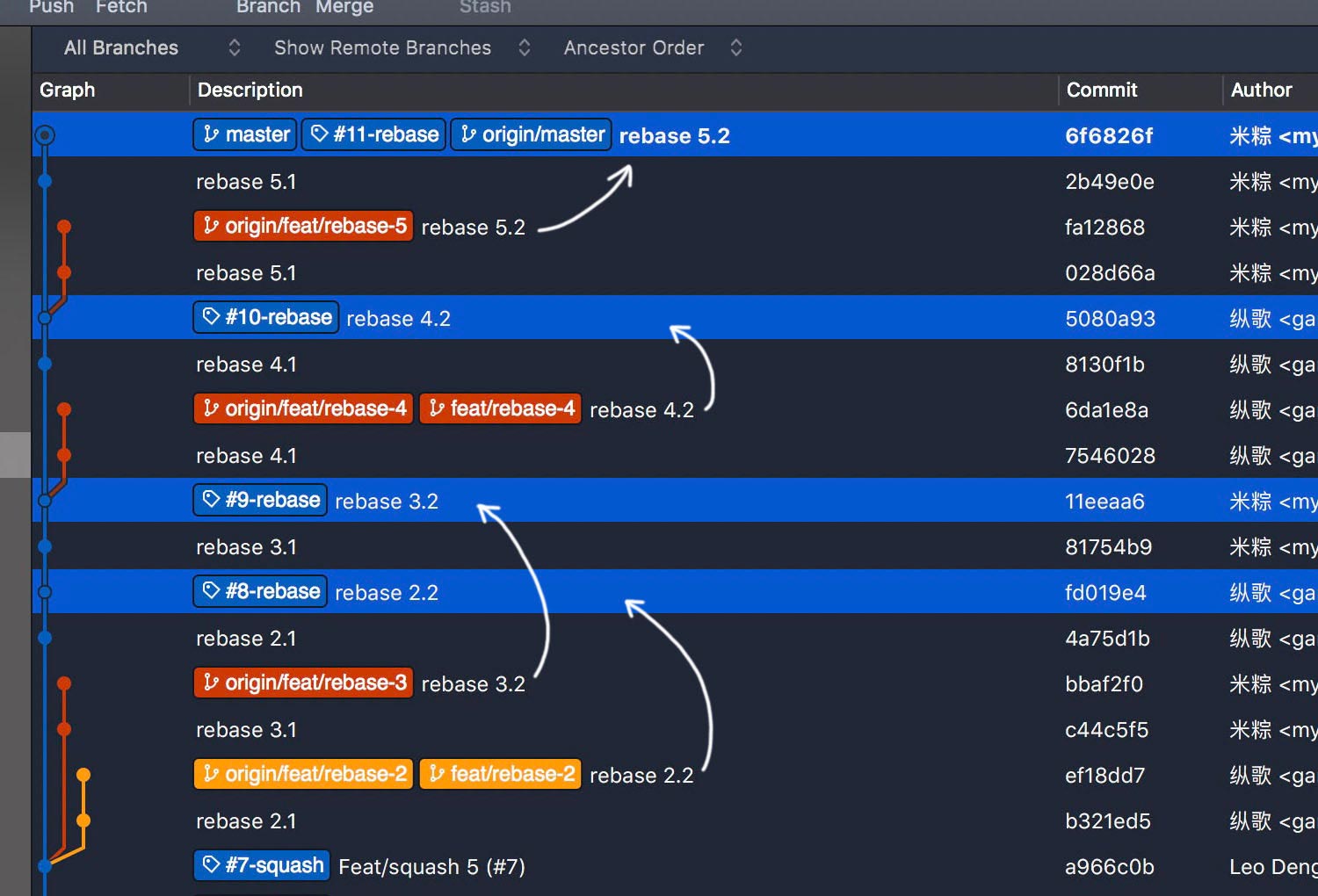

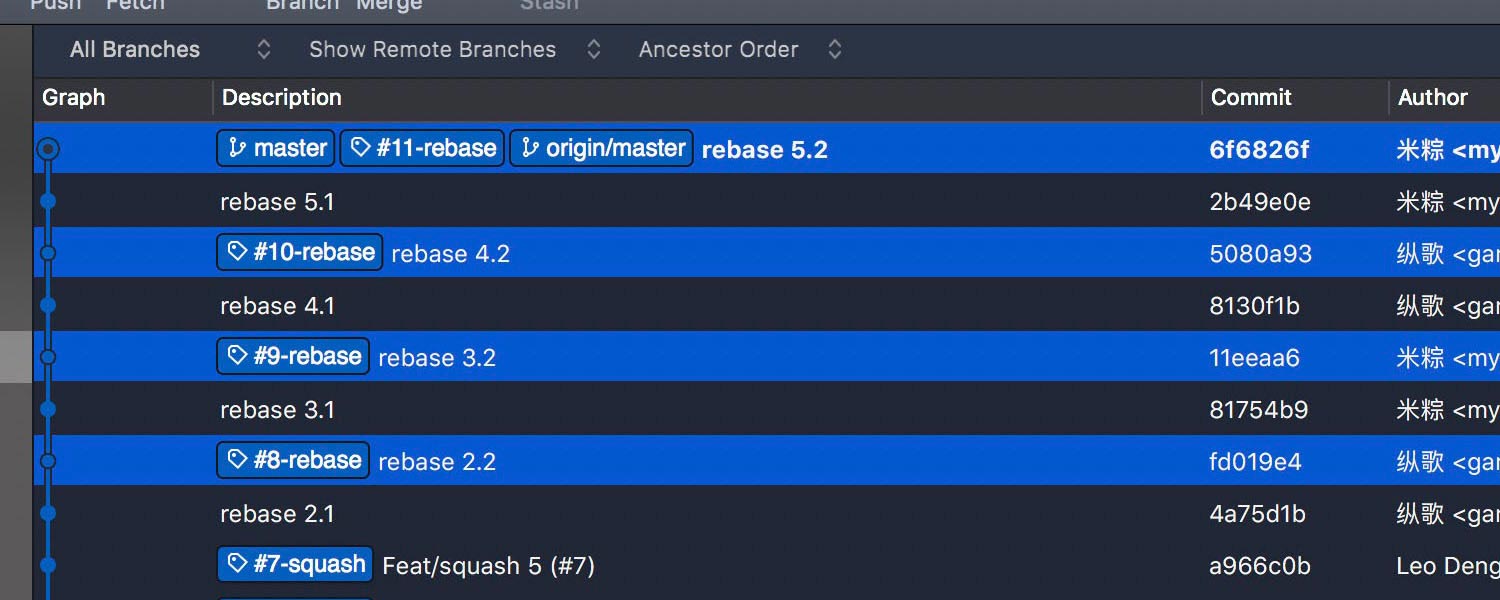

How about rebase mode? Let’s submit some PRs in exactly the same process. PR #8 and #9 in parallel, #10 and #11 sequentially.

Development details are retained after housekeeping work. But cooperation details are lost.

You may want to argue that all the details are just hidden, not lost since they could be found on GitHub. As of the merged PRs, true. But that’s not reliable, you’ll get it once you have migrated repositories to another platform. Even forking a repository on GitHub could make the hidden details untraceable, in a way.

The only reliable approach is, to retain all the details in a closed cycle within the git repository. That being said, GitHub (or GitLab, BitBucket, etc.) is, and should be, just an opt-in. How could that happen?

Merge mode is the winner.

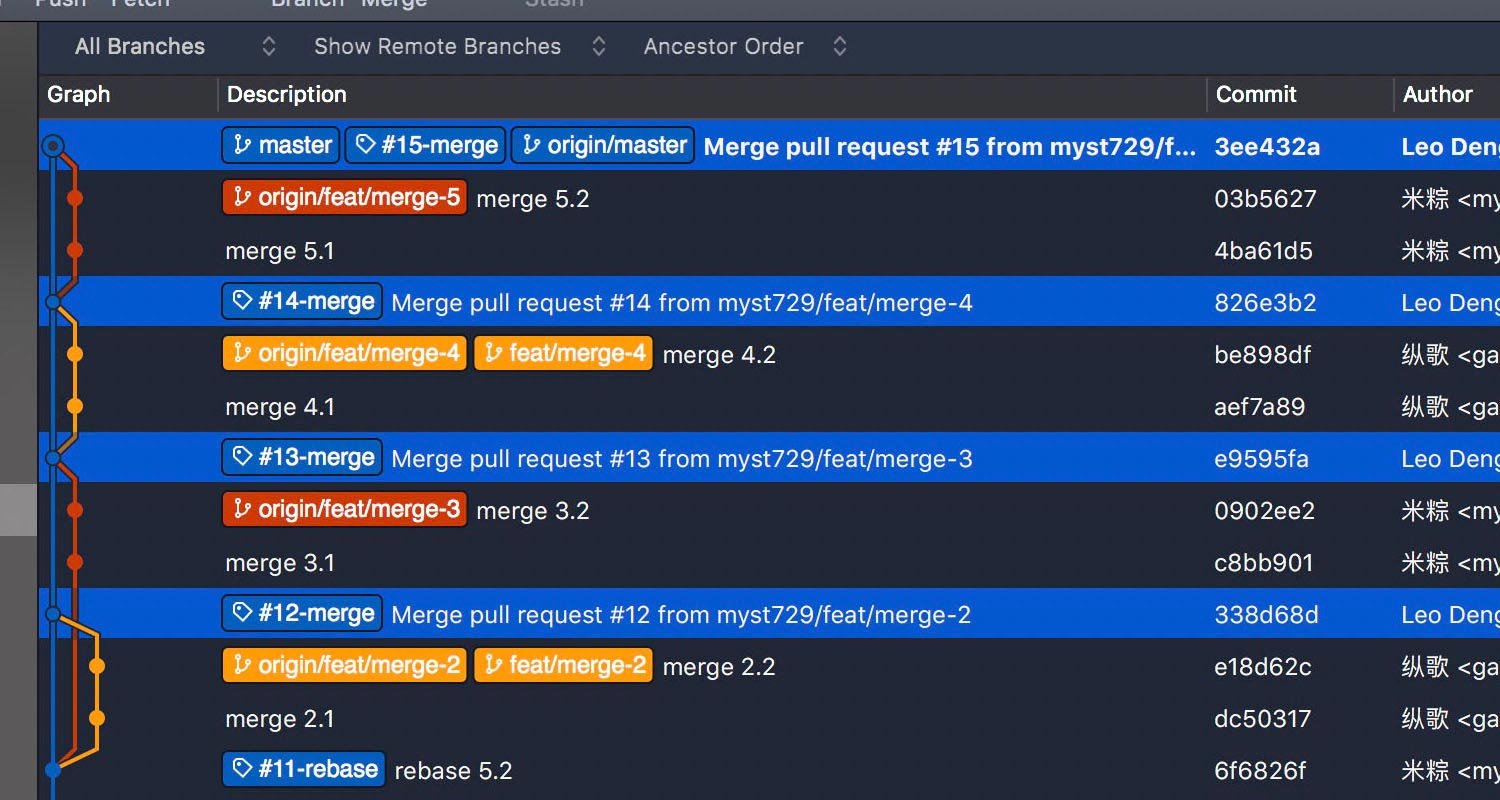

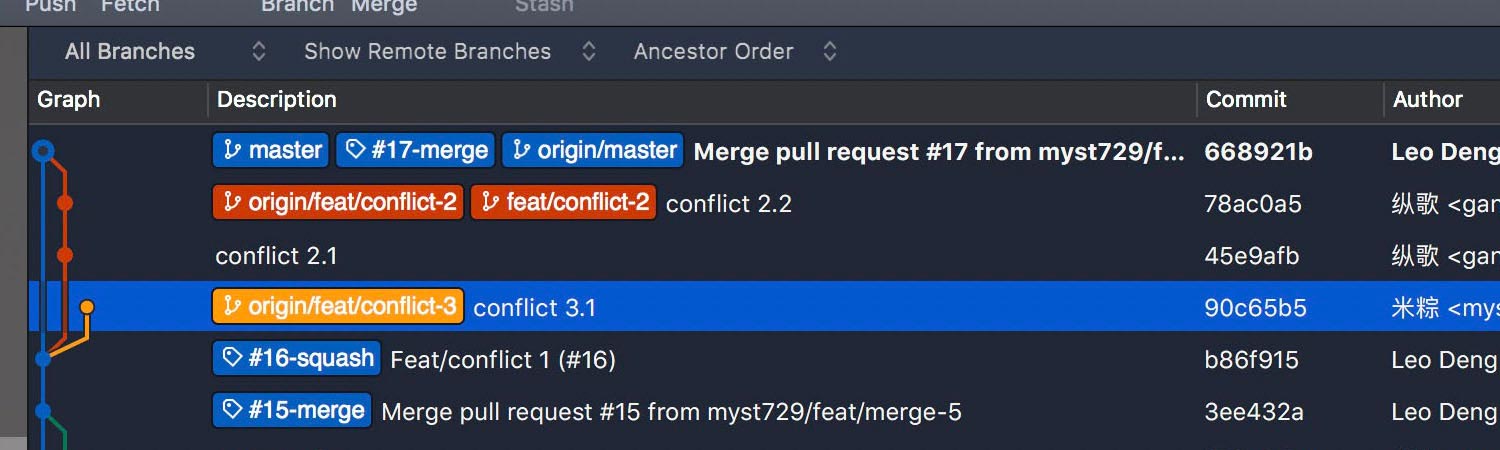

Let’s repeat the whole process, in merge mode.

And the details are still there after the housekeeping work. Thanks to the --no-ff option.

Now, let’s get back to a repeated criticism – the sideway out-and-ins. Are they really that ugly? What is the best way to interpret the log graph?

Just remember the rule – always focus on one color. The primary branch master is in blue, while each sideway has a different color. It is how “ugly” the sideways are that makes the history of development, the dependant and relier crystal clear. Once you manage to read the log graph, it’s not messy or ugly at all.

Wait, what about the conflicts?

We didn’t mention that topic, did we? Conflicts bring more sideways so conflicts must be ugly too, right? I don’t think so. Conflicts are common facts in a project. They reveal secrets not only about the repository but also the project itself as well as the team behind. The architecture, the requirements management, the task splitting and assigning process, the development guidelines and cooperation model within the team. Conflicts reflect them all, if you treat conflicts the way they are.

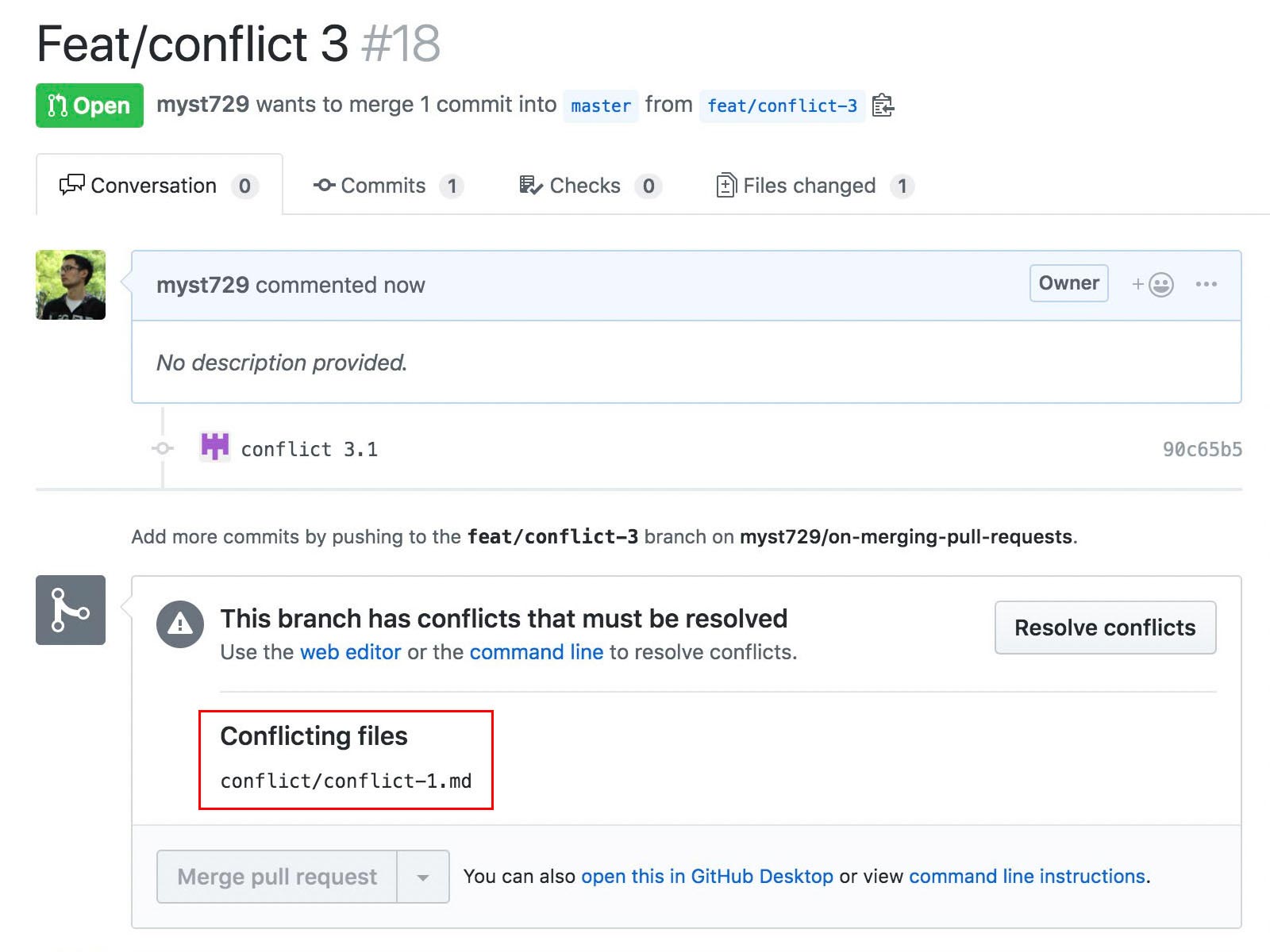

Take a look at an example – branch feat/conflict-3 has conflicts with master.

Thus, the PR created from feat/conflict-3 couldn’t be merged into master – the merge button is disabled.

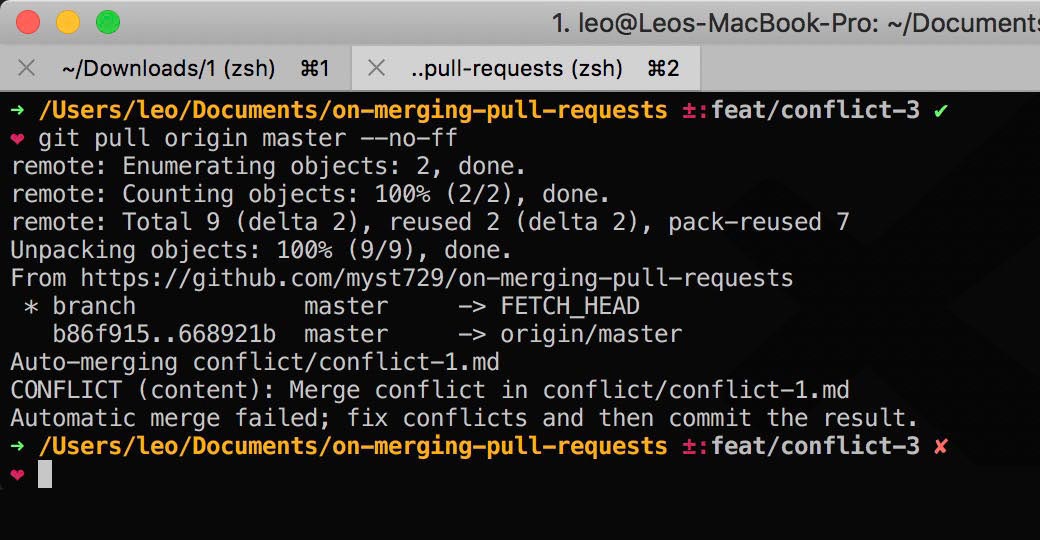

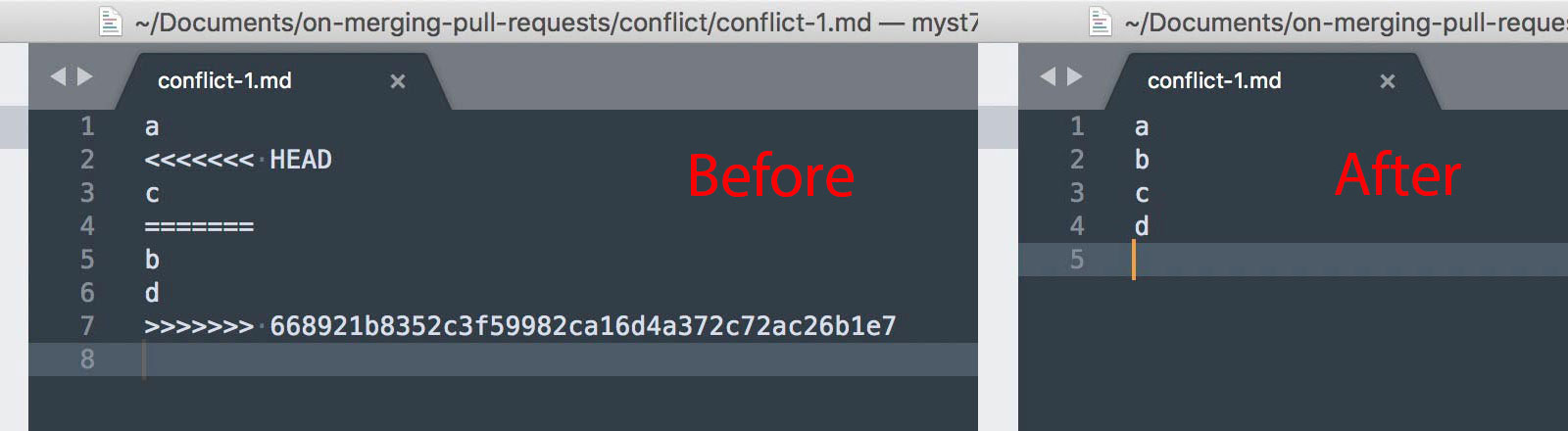

What we need to do is to resolve the conflicts:

-

Fetch

masterand merge intofeat/conflict-3.

-

Resolve the conflicts manually, since automatic merge failed.

-

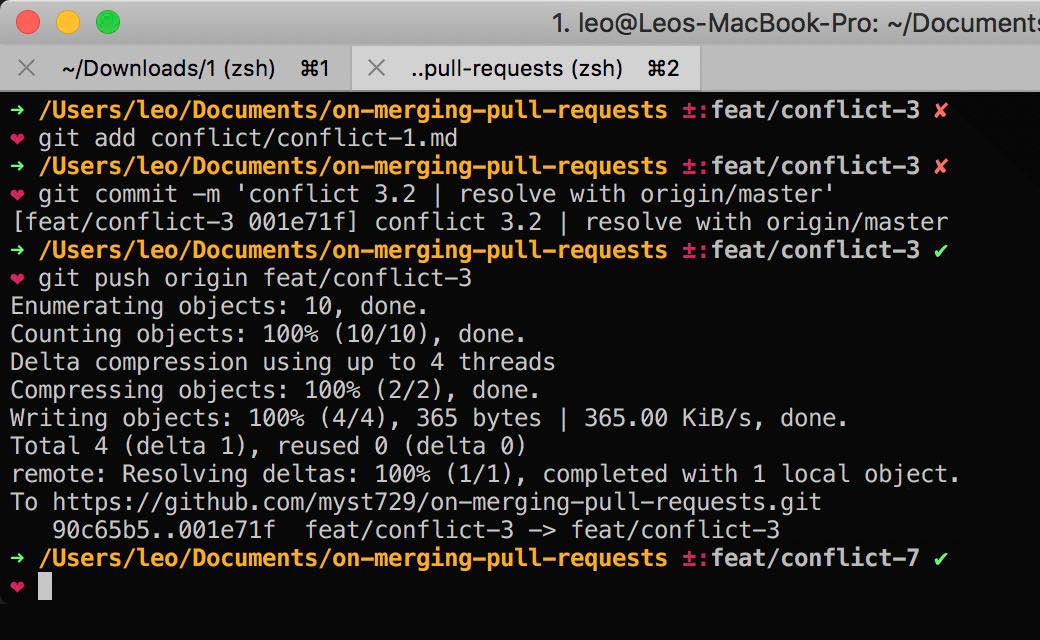

Commit and push again.

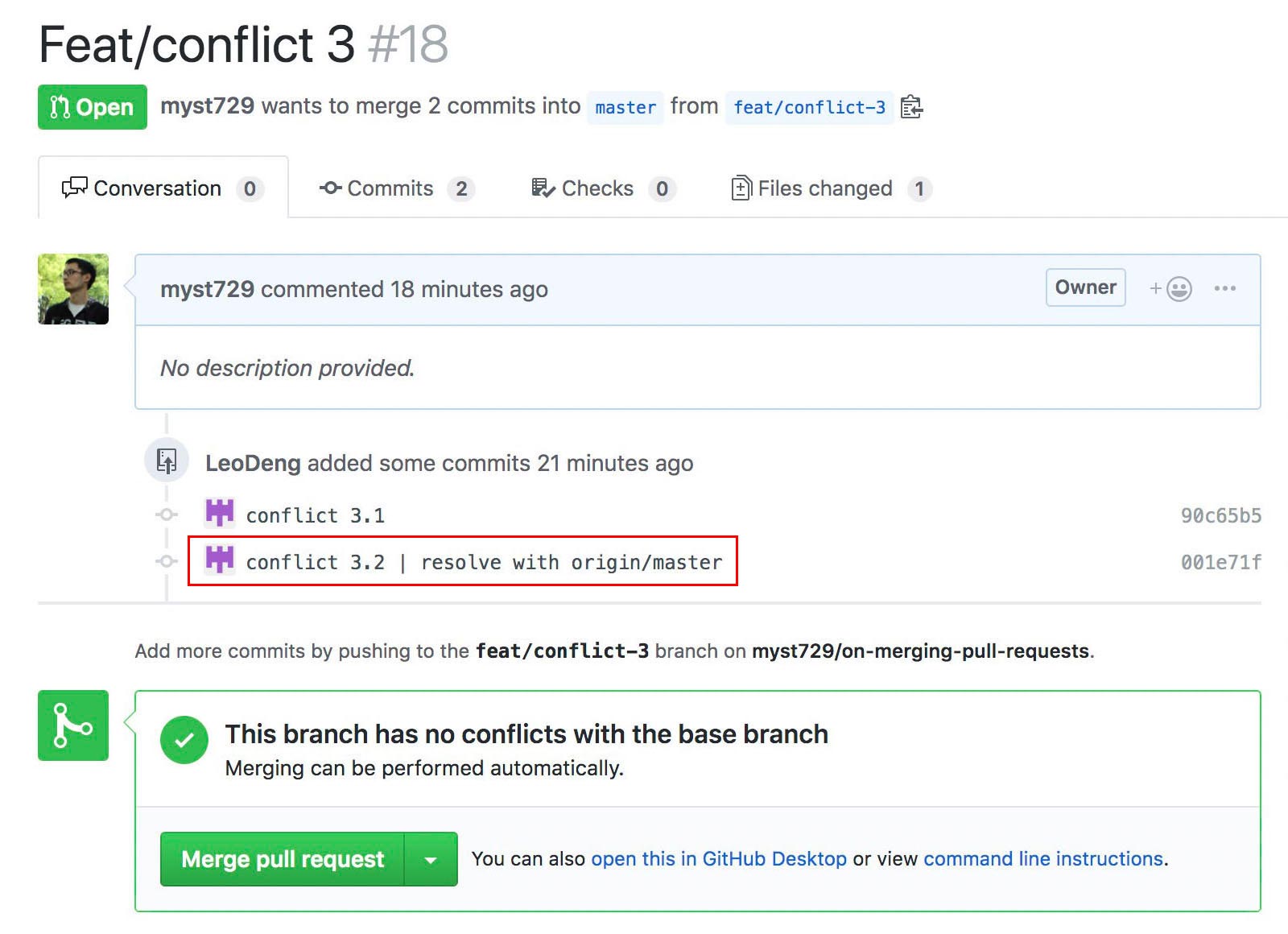

Now, with the second commit, the PR is ready to be merged.

Let’s revisit the question, are conflicts ugly? Sort of. Or maybe we shall ask another question – is ugliness the key focus in dealing with conflicts?

No, it’s not. The key focus is the fact – conflicts, and why. Are there problems with abstraction and reuse? Are the features mutually independent or really should be one?

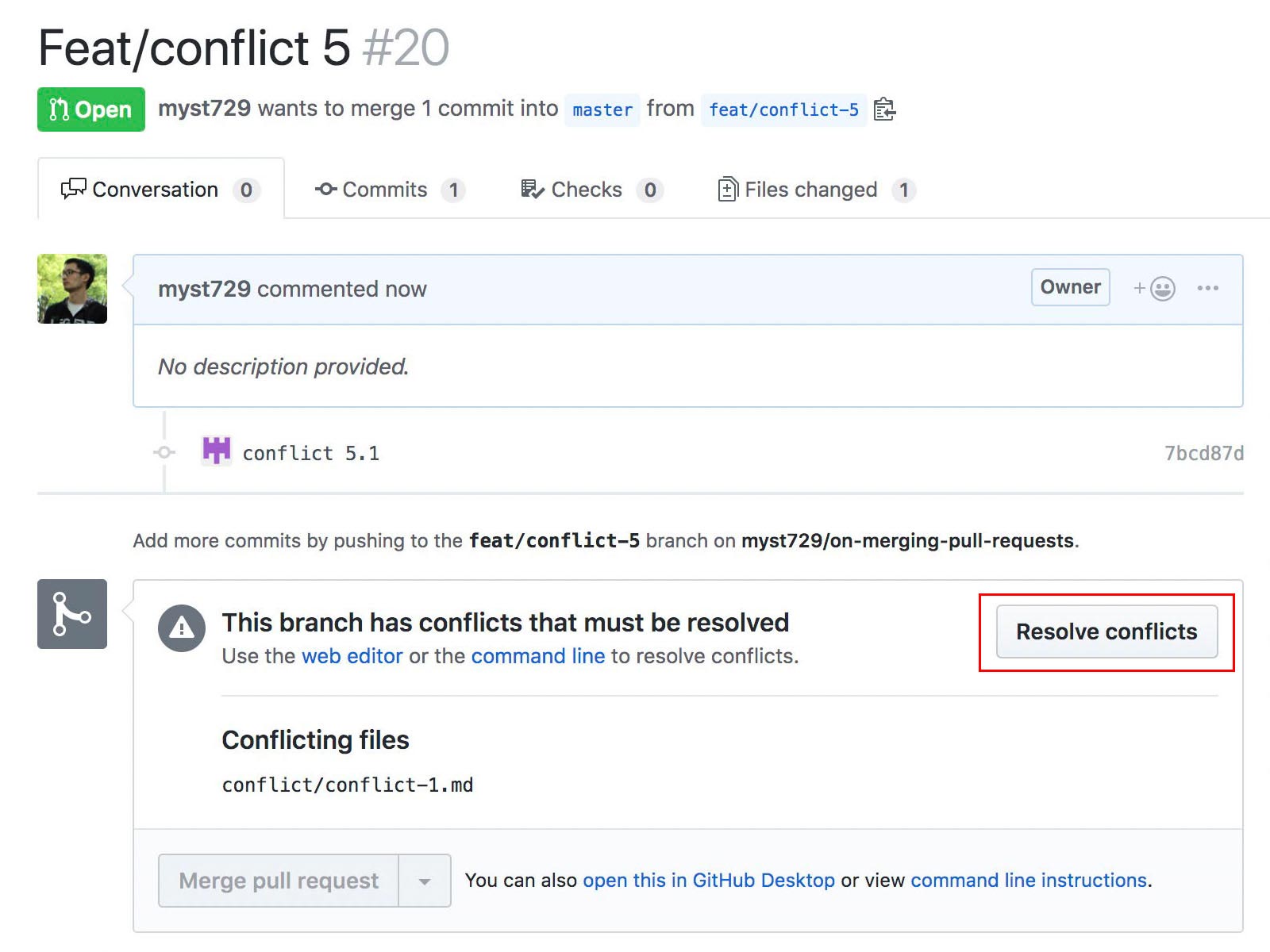

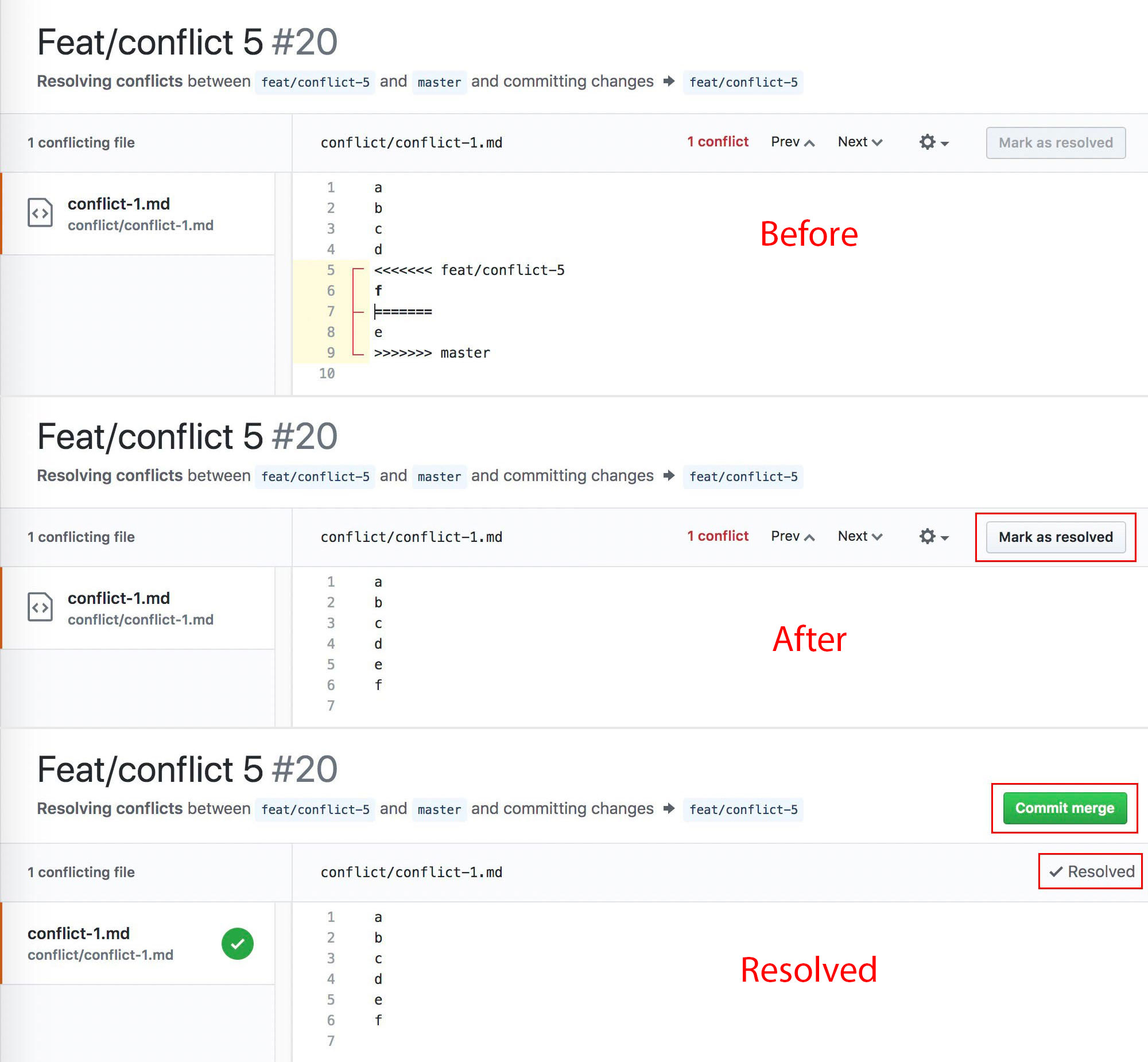

How does GitHub deal with the conflicts?

GitHub allows you to resolve conflicts online. Let’s see how it handles the job. Repeat the process, but this time we use the tool provided by GitHub.

Resolve manully and commit, very similar.

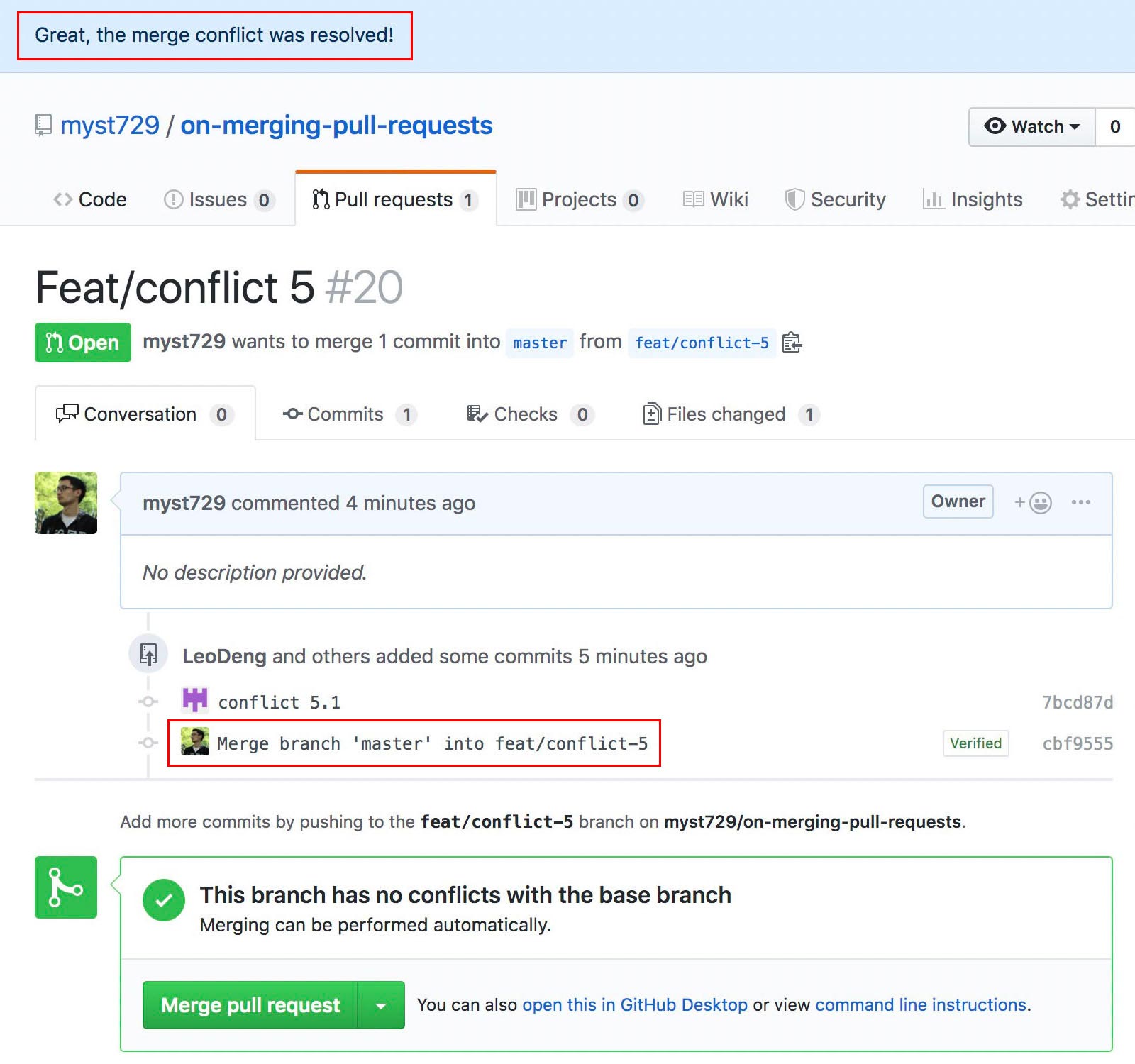

Another commit is added. Conflicts resolved.

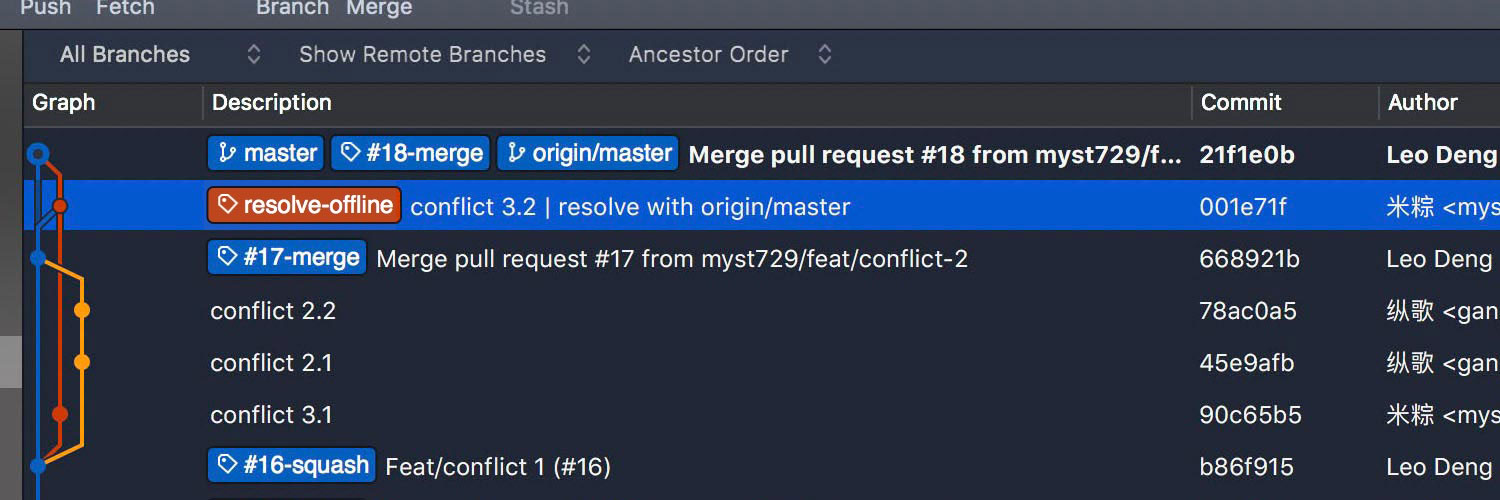

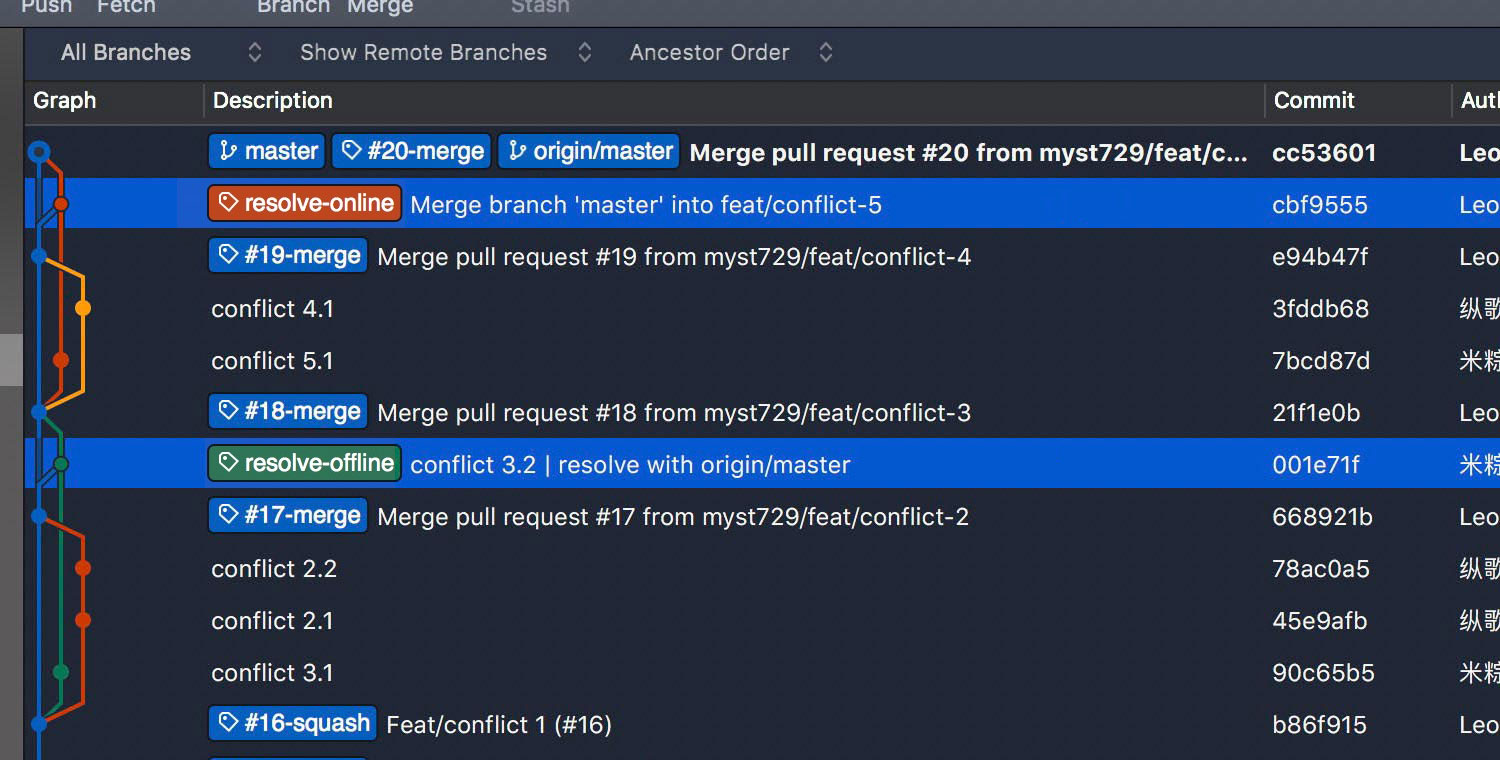

Compare the log graph. GitHub does exactly the same as we did offline. Surprised?

With or without --rebase?

When we resolve the conflicts offline, we pull master branch with --no-ff option. Now, let me ask you a question, what would happen if we pull with --rebase option? Think twice, they are very different.

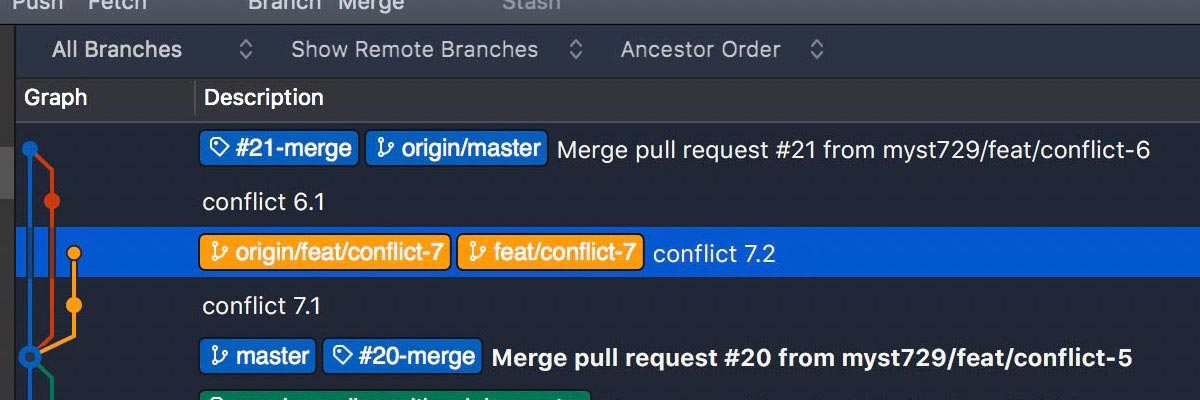

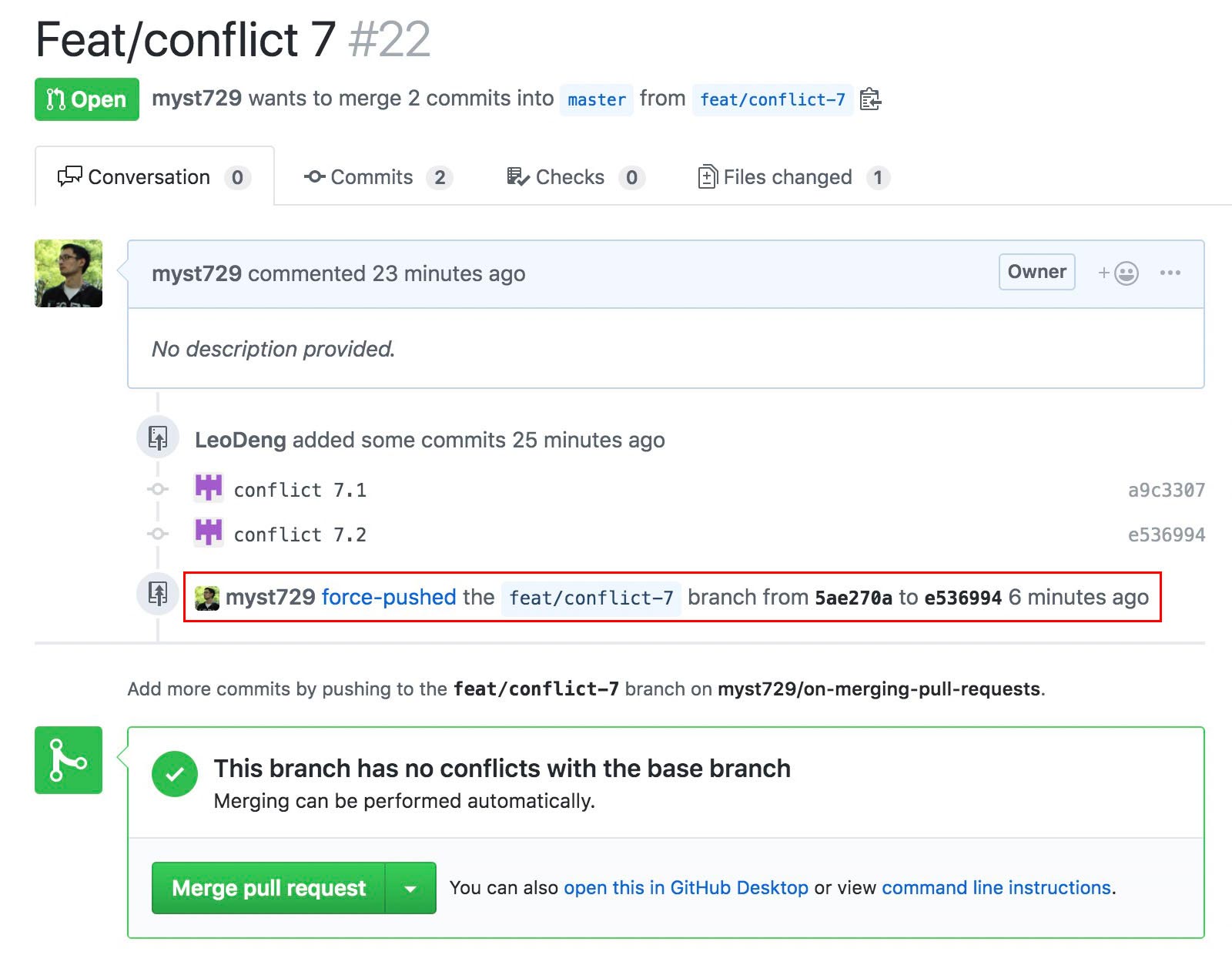

Once again, a feature branch that conflicts with master.

-

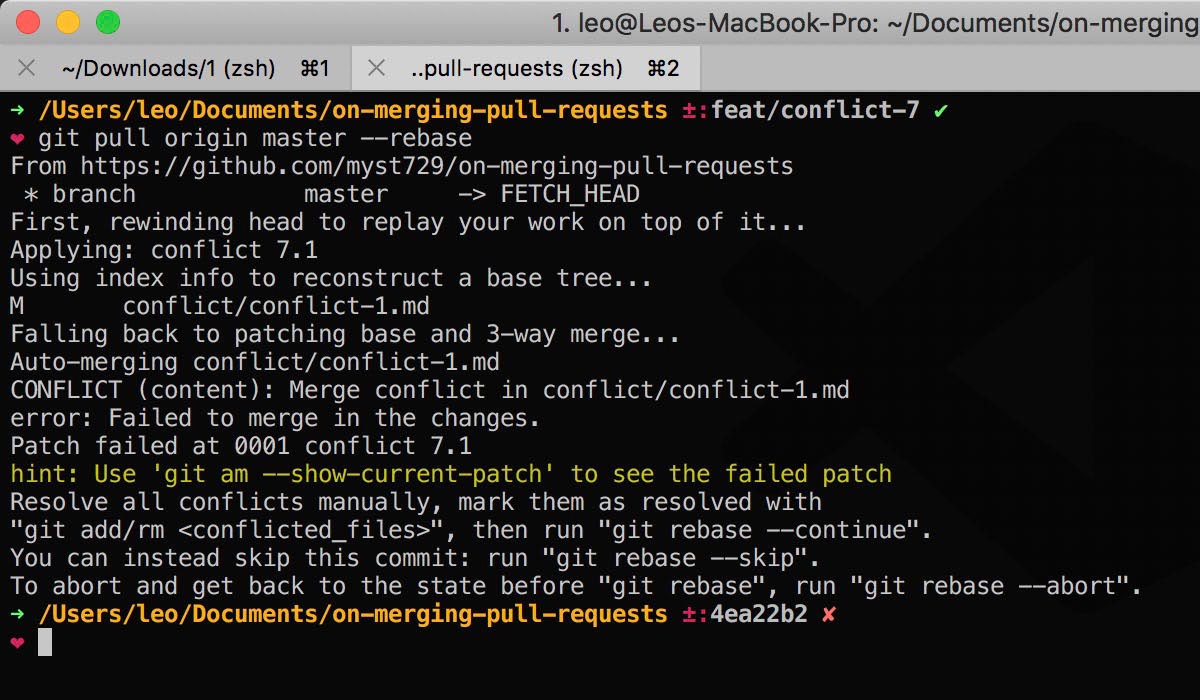

Instead of pull with

--no-ff, we use--rebaseoption.

-

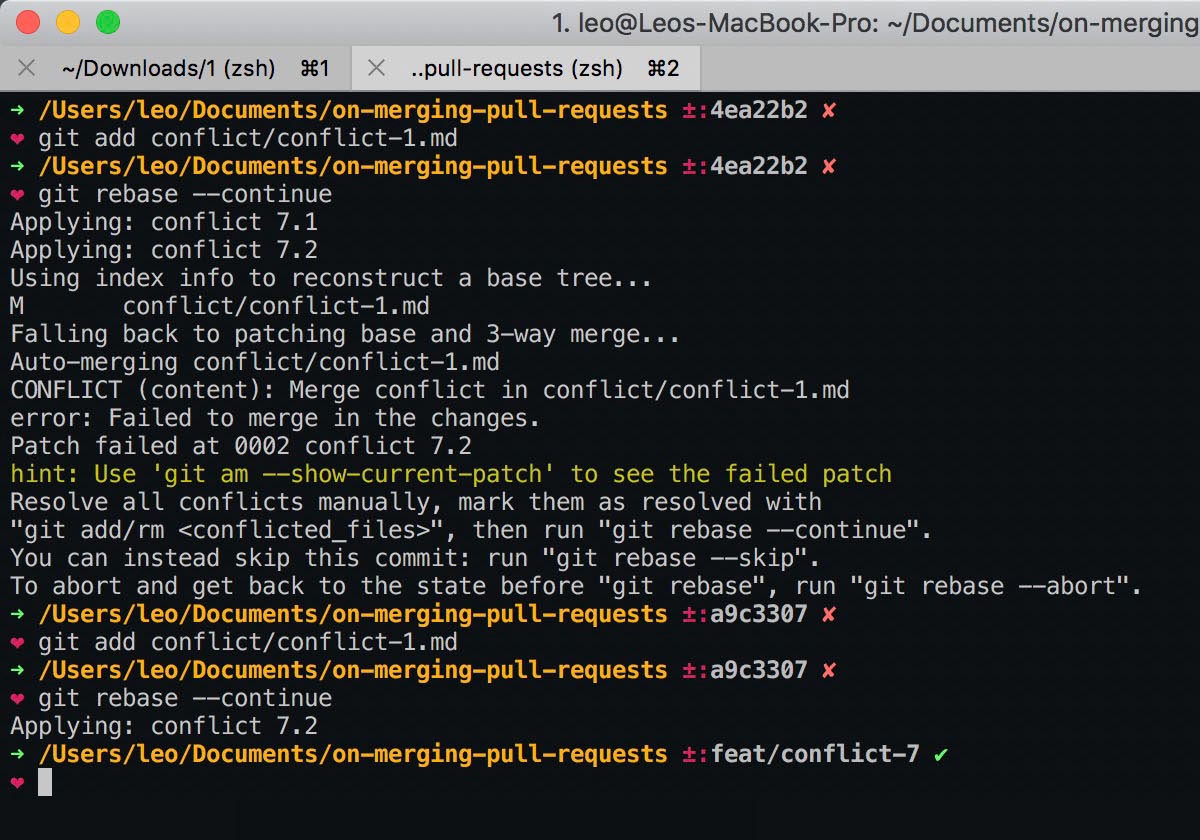

Resolve the conflicts.

-

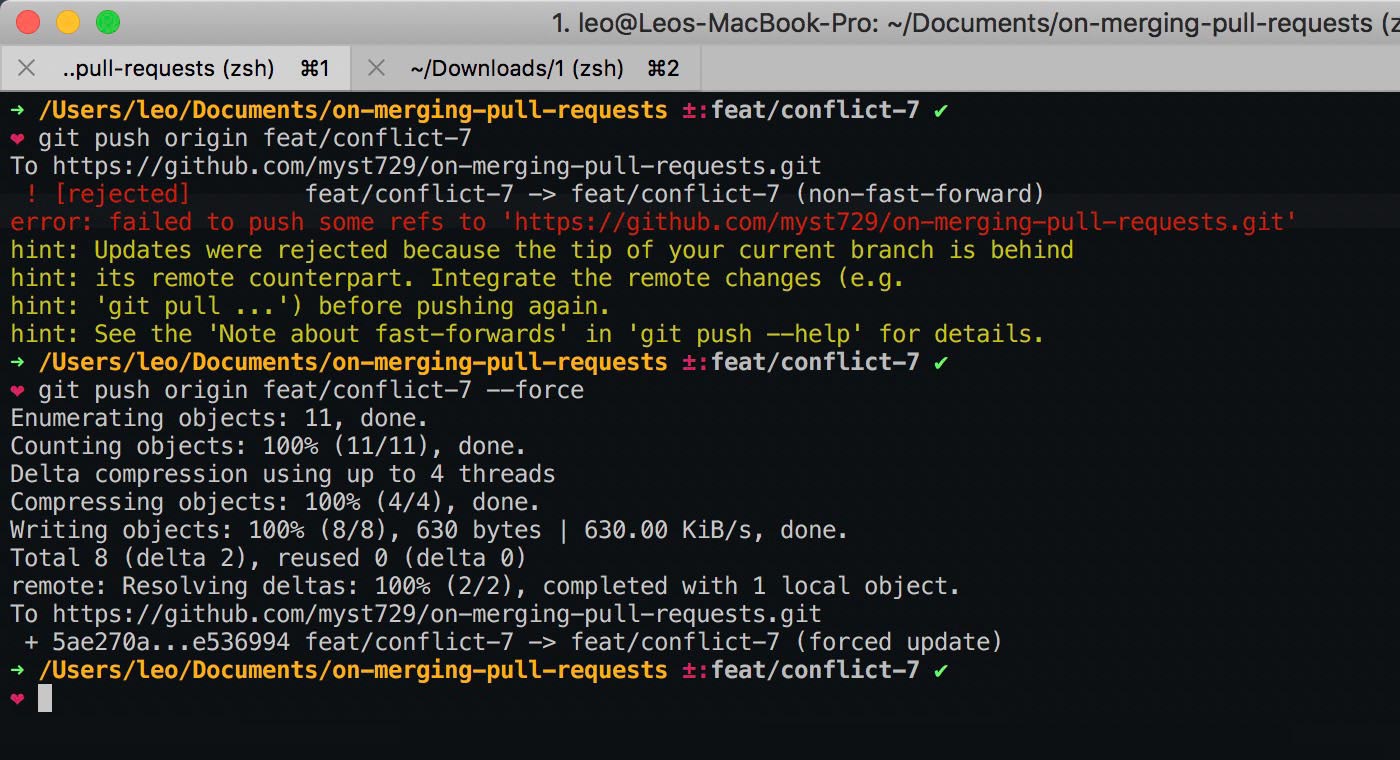

Force push, since local

feat/conflict-7is no longer aligned with remotefeat/conflict-7.

-

Now we could merge the PR on GitHub.

The PR is eventually resolved and merged. Great! Works just fine.

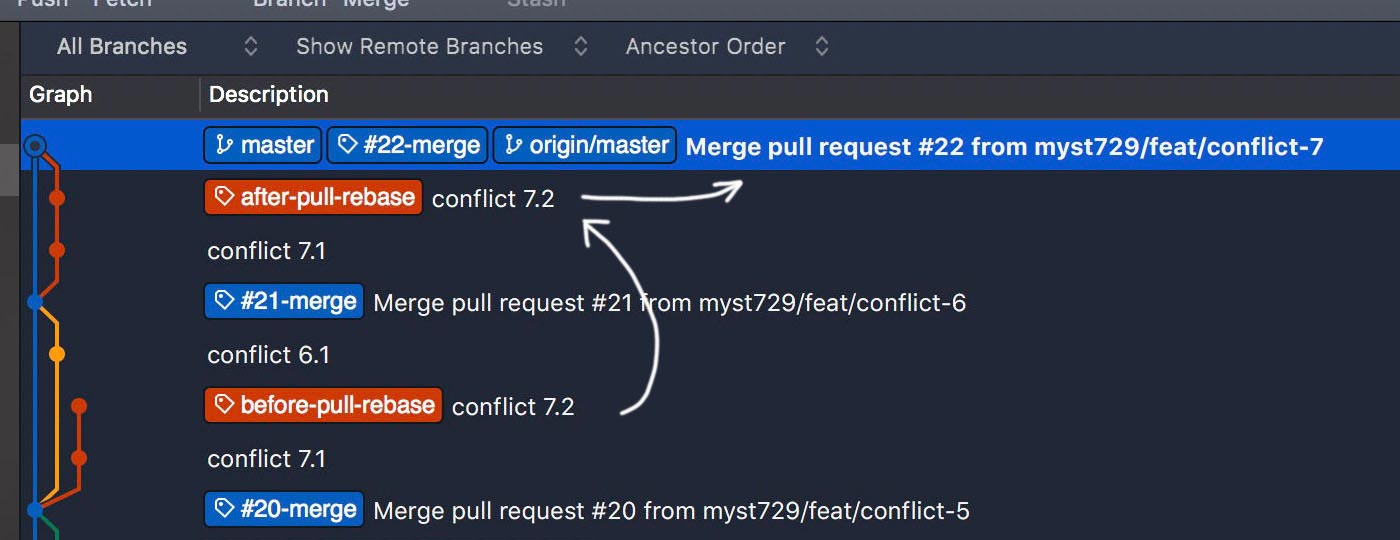

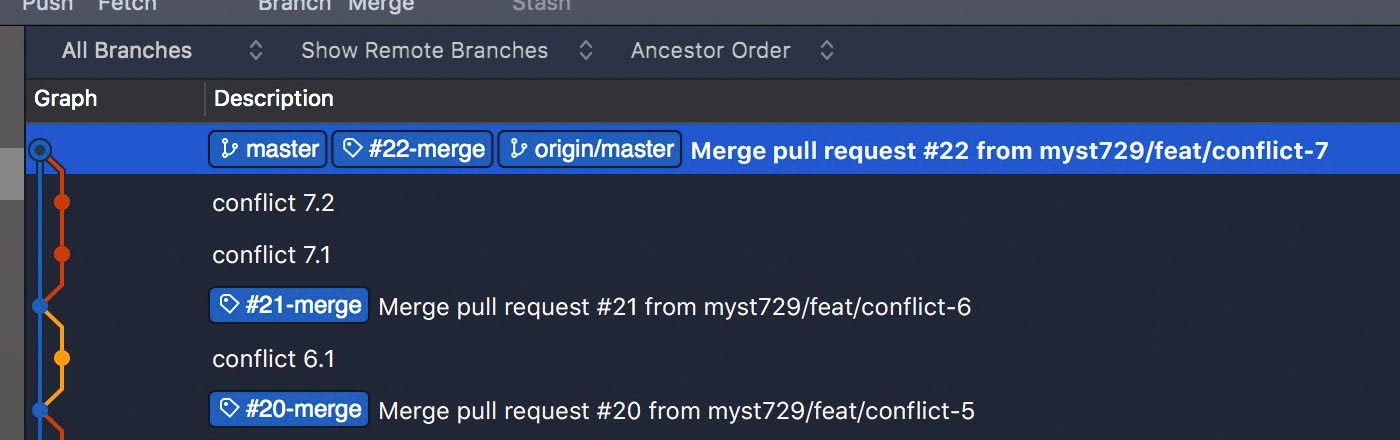

To be clear, I tagged the commits before and after git pull --rebase. What if we never did that? Let’s remove the tags.

Conflicts? Not quite like that – just two sequentially developed features. Information lost again. And more importantly, the git history fails to fit the facts.

Are rebase and squash completely wrong?

No, that’s not what I’m trying to sell. Sometimes we don’t have to keep every piece of (distracting) information. For those cases, rebase and squash may cause information loss, which is fine. For instance, a series of dependency updates, fixing typos in changelog, etc. Personally, I use rebase a lot to resolve such issues offline. In rare cases, I also use rebase --onto to fix wrong branching and merging (may cause code loss, which is not a bug if you know how git works in the nutshell).

I’m just suggesting that “not using rebase mode and squash mode to merge a PR on GitHub”. They form a well-design model together with GitHub Flow, but you lost history details. GitHub keeps a backup of your lost details in PR, then you or your team are tied to the platform (very smart business model, honestly).

Conclusion.

Projects in the real world could only be much more complicated than the examples above. Apply merge mode in most cases, and don’t be afraid of conflicts.